MAKING HIS POINT

A LIFE-CHANGING EXPERIENCE PLAYING FOR THE TAR HEELS PROMPTED TOM KEARNS TO CREATE A FIRST-OF-ITS-KIND ENDOWMENT

By: Adam Lucas

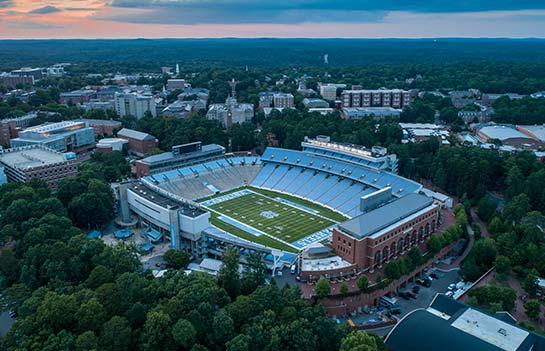

When Tommy Kearns committed to the University of North Carolina in the spring of 1954, he’d never been farther south than Washington, D.C. Kearns grew up in the Bronx, the capital of the basketball world in the 1950s. He’d never seen a North Carolina game on television. He knew nothing about the campus. The priests at his prep school, St. Ann’s Academy – which would eventually become the basketball powerhouse Archbishop Malloy – wouldn’t even send his transcripts to Carolina.

But Kearns knew Frank McGuire. The popular St. John’s coach was leaving New York and was considering taking the head coaching job either at Carolina or at Alabama. McGuire was an attractive coaching candidate, because his relationships with New York City recruits meant he would arrive on campus with a solid recruiting class – Kearns, Joe Quigg, Bob Cunningham and Pete Brennan were the likely members – already arranged.

“If he had gone to Alabama,” Kearns said, “we’d all have probably gone to Alabama. Thank goodness he made the wise choice.”

Thank goodness for Kearns and his teammates – and for the University of North Carolina. Sixty-one years after Kearns was the starting point guard on the 1957 UNC team, the first Tar Heel team to win an NCAA championship, he and his family are part of another first – they’ve committed to the first position-specific endowment for men’s basketball.

The Tommy Kearns Point Guard Endowment will specifically fund the point guard position for the Tar Heel basketball program. Along with his wife, Jane, and daughter and two sons, Kearns felt it was important to make a unique commitment to the program that helped change his life.

He’d considered transferring as a sophomore, when he averaged just six points per game. McGuire helped Kearns understand the importance of playing as part of a team rather than an individual. The coach used to needle his point guard that the Tar Heels actually needed two basketballs – one for Kearns and one for the other four players on the court.

“Frank McGuire changed my life,” Kearns said. “If I had not gone to Chapel Hill, I wouldn’t have received the kind of instruction that I got from him. He took a kid who was probably a little carried away with himself and helped me put myself in perspective with the program and with my teammates.”

Of course, McGuire also changed Kearns’ life by providing him with one of its indelible moments: being part of the 1957 national champions. That team finished 32-0 and won back-to-back triple-overtime games on back-to-back days in the national semifinal and national championship game.

Kearns played all 55 minutes in the semifinal win over Michigan State. He wasn’t pleased with his performance, and he knew his team would face a formidable Kansas squad in the title game. The Jayhawks featured Wilt Chamberlain, the dominating center who would be playing in front of a largely pro-KU town in Kansas City.

But Kearns had a feeling about the Tar Heels.

“I know we’re underdogs,” he said the morning of the 1957 title game (he was right – Kansas was almost a 10-point favorite). “But we’ve come too far. We’ve won too many games that we should have lost. We beat South Carolina early on, we beat Maryland, we beat Duke at home. Even last night, I had a horrible game and we still won. It can’t end with a loss. It just can’t. It’s not going to happen. We’re going to win the game tonight.”

And, of course, he was right. McGuire, always looking to challenge his players, cornered Kearns at the pregame meal.

“Are you afraid of Chamberlain?” McGuire asked Kearns.

“No, sir,” his point guard replied.

“Good,” the head coach said. “Then you’re jumping center against him.”

Kearns was 5-foot-11. Chamberlain was seven feet tall. As McGuire expected, the sight of Kearns lining up in the jump circle against Chamberlain caused a ripple to go through the Kansas City crowd. And perhaps it put just the slightest bit of doubt into Chamberlain’s mind. On a night that was decided by the smallest of margins – the Tar Heels won a 54-53 decision in triple overtime – McGuire knew he needed every possible advantage.

Kearns remains proud that the first three of Carolina’s national title teams were run by a point guard from the New York area. Jimmy Black helmed the 1982 squad, and Derrick Phelps was the lead guard on the 1993 team.

And now, with the Tommy Kearns Point Guard Endowment, he’ll have a critical connection to the next national championship point guard, too.

“Coach Smith is responsible for so much of how the players feel about the Carolina basketball program,” Kearns said. “And Roy Williams has been able to continue that and even take it on to the next level. Everyone is so proud of the fact that they played at Carolina and were part of that program. It’s embedded in you when you play for Carolina. That’s why Jane and I wanted to make a financial commitment to basketball.”

Having former players involved in such a financially substantial way is a relatively new phenomenon for Tar Heel basketball. Taking a leadership role in that process was important to the Kearns family.

“We wanted to do something special,” Kearns said. “We especially liked it because it’s the first of its kind, and we hope it will prompt others to do something similar.”

Williams knows that while the gift is important for men’s basketball, it has a tangible impact on every sport in the Carolina athletic department.

“The fact that our former players feel this way about Carolina basketball is something I love,” Williams said. “I’m so appreciative of that. I’m also appreciative that anything someone does for us makes it easier for other sports. If someone endows a scholarship for men’s basketball, that helps our budget and I don’t have to worry about hurting another sport if I do something for men’s basketball. So a gift like this shows Tommy’s love for the basketball program, but it also shows his love for the entire University of North Carolina.”

The Rams Club plans to honor Kearns and his family at an upcoming home game, where most fans will recognize him for his on-court exploits. It’s possible that his off-court contributions might last even longer.

“My scholarship in the 1950’s was a pittance compared to what it costs now,” he said. “We want Coach Williams to be able to run this program the way he wants. It was one of the great privileges of my life to be able to come to the University of North Carolina. I’m so happy that I’m able to give something back to those who gave so much to me.”

More Stories

The impact of giving comes through in wonderful stories about Carolina student-athletes and coaches, as well as the donors who make their opportunities possible. Learn more about the life-changing impact you can have on a fellow Tar Heel through one of the features included here: