THE FRUITS OF HIS LABOR

JASON BROWN MADE A SEAMLESS TRANSITION FROM FOOTBALL TO FARMING IN ORDER TO ACHIEVE HIS DREAMS

By: ADAM LUCAS / Photos by: J.D. LYON, JR

Jason Brown is on a farm, and that’s not very surprising.

His mother worked tobacco and cotton for most of her childhood in Vance County.

His father grew up in Yanceyville on a farm that produced sugarcane.

Before Jason’s sixth grade year, the family moved to a farm on 45 acres outside of Henderson.

Six and a half of those acres were grass, and his parents immediately assigned Jason the job of mowing it.

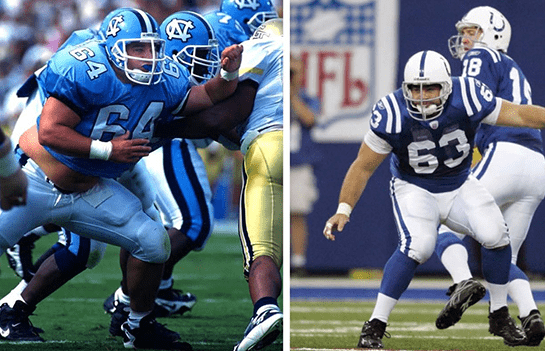

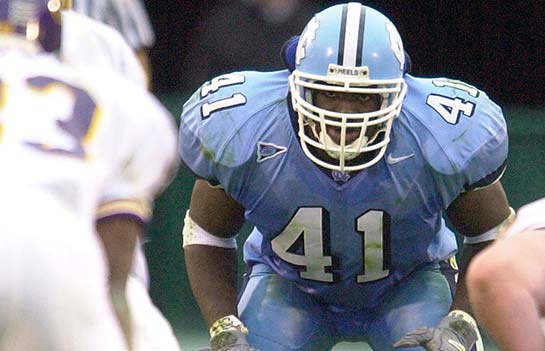

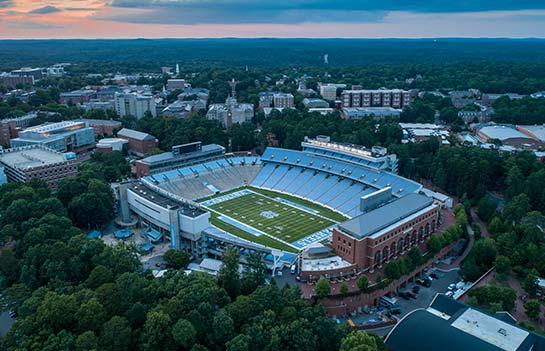

During Brown’s first few days on campus at Carolina in the summer of 2001, his new Tar Heel teammates called him “J-Brown.”

After getting to know him, however, they altered the nickname to something a little more befitting his down home personality: “J-Bama.”

So his college and professional teammates long knew he was likely to spend some time on a farm after football. His wife, the former Tay Dickens, knew her husband was passionate about farming.

But this farm? This 1,000 acres in Louisburg? No one knew he would end up here. And no one knew that Brown would work the land from daybreak to nightfall, then get up the next day and do it all over again, just for the chance to give everything away.

Brown’s family had already introduced him to farming and to the importance of helping others. It was reinforced at Carolina, where he was a regular on the football team’s voluntary Friday trips to the North Carolina Children’s Hospital. That’s when he began to internalize the importance of service.

“It made such an impact on me,” Brown says. “One day, we went over there and we met a little girl who had just been in an accident with her father. Less than an hour before, they had told her that her father didn’t make it. She had just received the worst news of her life, and there we were trying to share a little bit of love and hope. We were able to give her a big hug and put a little smile on her face, and I will never forget that.

“It’s little things like that that resonate and make you realize how human we all are and that we are all interconnected.”

Another situation at Carolina reminded Brown of the importance of putting others first. In the fall of 2003, the Tar Heels visited Wisconsin and absorbed a 38-27 loss. The next day, Brown learned his older brother, Lunsford Brown, had been killed in action in Iraq.

Upon hearing the news, the Tar Heel head coach, John Bunting, drives Brown back to Henderson. Bunting drives, Brown sits in the passenger seat, and Tay rides in the back seat. Bunting spends hours in Henderson that afternoon, listening to stories about Lunsford and sharing hugs and tears. Sunday is a big meeting and film day in college football. Bunting doesn’t meet or watch film. He just visits.

The next week, Carolina loses to NC State, 47-34. The next day is Lunsford’s service. Bunting brings the entire team to Henderson for the funeral. Even now, 14 years later, Brown’s eyes moisten a little when he tells the story.

“They came in and they cried just as much as I did that day,” he says. “My offensive line coach, Hal Hunter, was tough as nails. He would never let you see any emotion coming from him. He cried like a baby. I soaked up all that energy. When I committed to Carolina, Coach Bunting told me, ‘Family first.’ I’ve heard those words a lot of times, and I knew there would come a test. Coach Bunting lived it. When it came to leadership of the players and teaching lessons, he was the best. At my lowest point and darkest moment, he showed me what it meant to care about other people. He is definitely one of my heroes.”

Brown would go on to a long and decorated NFL career. He played four seasons for the Baltimore Ravens and then signed a mammoth five-year, $37.5 million deal with the St. Louis Rams. He played three of those five seasons before being released.

At the time of his release, Brown was 28 years old. He had plenty of football left in him. Three teams were poised to make offers to secure his services; they were the exact three teams he and Tay had discussed as their dream locations. Baltimore was where he felt comfortable and had spent the first part of his NFL career. The Carolina Panthers were the closest team to his parents, and his mother was thrilled at the prospect of her son becoming a Panther. The San Francisco 49ers were close to Tay’s family in the Bay Area.

Brown turned them all down. He loved football—you have to love it to devote that much time and effort and physical commitment.

But it wasn’t his life. His life was just beginning.

“I was living the American dream,” Brown says. “My family was living the American dream. But we were leaving behind all the Americans. This is the greatest country in the world, but there’s still a lot of work to be done as far as sharing love with our neighbor. In my football career, I was entertaining people. Now I wanted to make a move to serving our community.”

Most people accomplish similar goals by devoting one day a month to picking up trash on the side of the road. Brown’s method was different.

“You have to understand that Jason is his own man,” says former Carolina assistant coach Ken Browning, whose ties with him go all the way back to when Brown was being recruited. “He doesn’t base what he does on the worldly convention. He makes his own decision on what he thinks is the right thing to do regardless of how the world views it. And he has always had a positive outlook about people. Whatever he is engaged in, he is completely and fully engaged.”

Brown felt God was calling him to help hungry people. He told Tay he felt they were being called to put their house in St. Louis on the market and return to North Carolina. There were skeptics, of course. Plenty of people told Brown he could feed thousands of hungry mouths with the money he would make from playing more football.

But that wouldn’t be fully engaged. Brown didn’t want to write a check. He wanted to touch the land and get his hands dirty. He wanted the satisfaction of being at the source of the solution. “God didn’t call me to finance the fight on hunger,” he says. “He called me to be there on the front lines.”

Very soon, he and Tay were driving the back roads of Franklin County. This was not a shock to her. She’d known she might end up somewhere similar ever since her first real introduction to the Brown family, over Thanksgiving of 2002, when they took her coon hunting.

The couple’s real estate agent showed them a tract of 1,154 acres near the Tar River. On the way to view that property, a bridge was out, meaning they had to take the long way. That’s when they passed by a storybook-quality farm, with rolling hills, white silos and a gorgeous farm house. “Whatever we are able to find,” Jason thought to himself as they passed by, “I hope it looks like that one.”

Brown was committed to his new vision, but he wasn’t impulsive. He and Tay looked at the Tar River land on three separate occasions. It was too close to a flood plain for his liking. Buying 1,000 acres of land isn’t easy. Buying the right 1,000 acres of land is even more of a challenge.

The family’s real estate agent was disappointed they didn’t like the Tar River tract, but he had an idea. “I know of another place,” he told them. “It’s not for sale, but the owners might be willing to entertain an offer.”

“You know,” the agent told them, “you might have even driven past it on the way here.”

And that’s how Jason Brown came to establish First Fruits Farm on 1,000 acres with rolling hills, white silos and a gorgeous farm house. As he walks the land with a couple of visitors, he’s still a little in awe that the farm he first coveted through his car window now belongs to his family.

It’s historic land, situated on a road named for the original owner. It had been in that family for more than 200 years, and was part of the original land grants through Lord Granville directly from the King of England.

But in all that time, it’s never been used quite like this. Brown had a vision.

“What you see here is about stewardship,” he says, gesturing at his land. “It’s about taking the blessings God gives us and using them as righteously as we can. That’s the covenant we made with God. We agreed

that whatever land we were blessed with, we would name it First Fruits Farm, and we would give away the first fruits of whatever is grown on the land.”

Brown started by watching YouTube farming videos. With the right mix of practical experience, guidance from his neighbors, and finding the right help, the farm is thriving. The first harvest, in 2014, yielded 120,000 pounds of sweet potatoes. In 2017, they harvested more than 250,000 pounds.

During his recruitment, Brown told Browning he enjoyed agricultural work and thought he might like to attend college somewhere he could major in that field. This was bad news for the Tar Heels, of course, because other in-state schools offered a more direct path to agriculture. Browning urged the young player to see a bigger picture.

“Jason, you’re going to need more than agriculture,” Browning told him. “You’re smart enough and talented enough that you’re going to need to be able to run the entire company. It might be an agriculture company, but you’re going to need to understand how the entire business works.”

That pitch made sense to Brown nearly 20 years ago. And now, here he is, standing on his farm just after dawn. He’s managing the replacement of a boiler just behind his farmhouse. The tractor needs more starter fluid. Dozens of people help First Fruits distribute the food raised here to those who need it. “We’re called First Fruits,” Brown says. “But really it’s All Fruits, because so far we’ve given it all away.” To date, that means the farm has generated 850,000 pounds of food for the hungry.

He’s speaking to a youth group later this week, and laughs when he says, “A lot of times, they look at me like I’m crazy,” when he describes his journey from the NFL to sweet potatoes.

The way they see it, he was living a dream, playing in one of the world’s most popular sports leagues, making incredible money, and reaching the peak of American sports recognition.

The way he sees it is a little different. Playing football gave him a platform and an opportunity. But the game was always going to be finite.

This summer, Bunting and Browning visited Brown’s farm. They stayed for over an hour, telling old football stories and telling some stories that had absolutely nothing to do with football. They remembered that before his senior season, Brown wrote a very pointed letter to the head coach. The Tar Heels had been 5-19 in the previous two seasons, and Brown wanted to make 2004 different. His letter wasn’t simply a dream. It contained concrete examples of what Brown needed to do in order to make a bowl game a reality—and, as Bunting recalls with a grin, it also contained some plainspoken advice for the coach.

Brown had a dream of going to a bowl game. The letter was his way of outlining his process. And during his senior year, the Tar Heels beat Duke, beat NC State, beat Miami, and went to a bowl game.

So Bunting didn’t drive away from Louisburg surprised that his former player had developed and cultivated an improbable dream and made it reality.

“My takeaway from visiting Jason this summer is seeing just how much he believes in his fellow man,” Bunting says. “It’s seeing just how much he dreams of doing right by others and being a blessing on earth. He has tremendous pride, and he has lots of dreams and lots of goals. He has dreams for that entire property, and what he can do with it to help the surrounding communities. And no one should be surprised when he achieves all of those goals.”

This story appeared in the DECEMBER 2017 edition of Born & BredMore Stories

The impact of giving comes through in wonderful stories about Carolina student-athletes and coaches, as well as the donors who make their opportunities possible. Learn more about the life-changing impact you can have on a fellow Tar Heel through one of the features included here: