SEIZE THE DAY

A SCHOLARSHIP TO NORTH CAROLINA CHANGED A.J. BLUE'S LIFE

By: Adam Lucas

It's a Monday afternoon in Dallas, North Carolina.

Two middle-aged men sit on a front porch on East Carpenter Street, smoking and warily eyeing a passerby. The passerby waves. They do not wave back.

Across the street from the house where A.J. Blue grew up, a boxer's heavy bag stands in the front yard next to a nearly-new patio umbrella that carries the Starbucks Coffee name and logo. A stark black and white sign issues a warning: "Surveillance cameras in use."

Six houses down, a home very similar to the one where A.J. Blue grew up is for sale. A toilet sits in the front yard. The asking price is $44,400.

The most recent complete state crime statistics and analysis are mostly from the year 2016. Gaston County, where Dallas is tucked just north of Gastonia, reported 25 killings that year. In 2016, the county's violent crime rate per 100,000 people was 473.5. The same rate for Orange County was 172.8; Wake County was 244.0. In 2012, Gastonia – placed among the nation's most dangerous cities by multiple polls – reported a violent crime for every 162 residents. The rate for Dallas was a violent crime for every 157 residents.

To put that in perspective, the rate for Chapel Hill in 2012 was a violent crime for every 673 residents.

"It was worse when I was growing up than it is now," Blue says frankly. Just around the corner from his childhood home was the neighborhood store. It's closed now, after changing hands multiple times in recent years, but everyone from the neighborhood remembers it. Ownership changed so frequently that locals didn't call it by a specific name.

"We just called it, 'The Store,'" says Roger Brown, who has known Blue since he was eight years old. "It was like a gas station without the gas. The guys who hung around that store, we grew up in a different lifestyle. Shootings and drugs were a daily thing in our neighborhood. As a kid, A.J. saw all of that."

The store was one of the centerpieces of the area's thriving drug trade. It wasn't unusual to drive by on a weekday and spot multiple school-age kids outside the store.

"I've coached for 40 years," says Bruce Clark, Blue's high school football coach at North Gaston High. "I don't know that I've ever coached in a community that had that rough of a place. I'm going to be honest with you. You had to be known, or you basically didn't go down there."

The store was approximately a first down from Blue's backyard.

He usually knew everyone who congregated outside the store. Everyone did. They were the neighborhood's superstars.

"I looked up to those guys," he says. "At one point, I wanted to be those guys."

He knows you will raise your eyebrows at this. A.J. Blue wanted to be the derelicts on the street corner? That doesn't make sense.

It doesn't make sense – to you, because you've never lived there. But now imagine you've grown up in Dallas and you're a kid who sometimes has to sleep in your car because there's nowhere to stay. You've gone to friends' houses to eat dinner not because you want to hang out, but because there is nothing – nothing – to eat at your house.

Now consider how you'd look at those teenagers on the street corner.

"The ice cream truck would come around, and someone would pull out a wad of money and feed the whole neighborhood from the ice cream truck," Blue says. "There could be 60 people standing there, and they'd buy ice cream for everyone."

The origin of the money wasn't important. The results of it were what mattered. It fed people. That's it. For one moment of one day, it fed people.

"So they were role models," Blue says simply.

It only sounds unusual in hindsight, that an impressionable kid saw these neighbors with questionable wads of cash as role models. At the time, it wasn't a story that he told. It was the actual life of a child growing up in North Carolina. Where is food coming from today? Maybe it's in the fridge. Or maybe it isn't, and maybe the guys on the corner will treat the neighborhood to the ice cream truck. It wasn't an isolated, one day phenomenon. It was daily life. It was A.J. Blue's daily life.

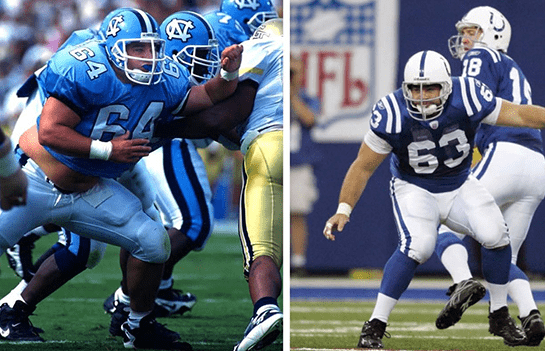

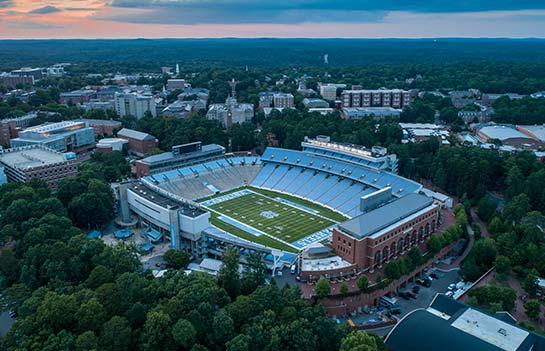

A football scholarship to the University of North Carolina allowed Blue to play in 40 career games. He scored 12 career touchdowns, after every single one of which the Kenan Stadium crowd chanted, "Bluuuueeeeeeeeee." He caught 29 passes and ran the ball 207 times and threw it five times.

He was a part of five Tar Heel teams that won a combined 38 games.

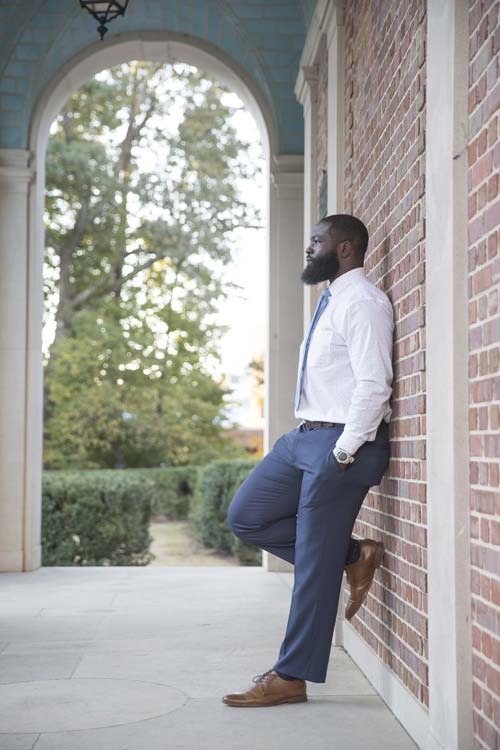

But it is likely that none of those are the most important byproducts of his scholarship. No, the most long-lasting result of his achievement is that it's a Monday afternoon in Dallas, and A.J. Blue is 159 miles away.

***

Bruce Clark spent the moments before one of the most important high school games he ever coached going through an escape plan with area police.

On Nov. 10, 2006, A.J. Blue quarterbacked North Gaston to the program's first-ever state playoff victory, a 55-30 win at West Iredell.

Six days later, Clark was at school, where he worked as a history teacher in addition to serving as the head football coach. He was well-known in the roughest neighborhoods of Gaston County. Many of his players didn't have transportation to practice or summer workouts, so he'd drive his pickup truck through the streets, picking up players to take them to the field. When he dropped them back off after practice, it wasn't unusual for him to give them a little extra food.

So it wasn't surprising that Clark would be one of the first to know about violence in Dallas.

Demarreo Beard was Blue's older brother and football mentor. He liked to ride dirt bikes, and he was friends with more than a few of those guys at the store, and Blue acknowledges his brother could sometimes be "reckless." Still, the younger boy idolized his brother.

On the morning of Nov. 16, 2006, Beard was simply sitting on the porch of a house in Dallas. Just sitting there, a normal day.

Multiple men drove up to the house, shot Beard several times, and drove away. He was dead before they left the scene. The reason for the murder remains murky.

Minutes later, Clark got a call in his office with the details of the crime. Clark immediately got A.J. out of class. It fell to the football coach to break the news of the tragedy to Blue, Blue's younger brother, and the boys' mother, Theresa Adams.

"I will never forget it," Clark says. "It was one of the hardest things I've ever done in my life."

North Gaston's next playoff game was the very next night at crosstown rival Hunter Huss. Rumors were flying and tensions were high. Gastonia remains a small town, and the two schools are just eight miles apart. The rumors virtually eliminated the time for grieving.

"The word was out," Clark says, "that if A.J. showed up at the game, he was going to be shot at."

Friday was gameday. Before lunch, Clark had already held meetings with the Gaston County police, the City of Gastonia police, and the town of Dallas police. The decision was made to take the North Gaston players out of class at noon. They were escorted to the game by police cars.

The head coach had a very frank conversation with Blue's family.

"Your family needs to talk about this," he told them. "I will support any decision you come up with."

"I'm going to play," A.J. said.

"You need to think about it," Clark told him. "I will never be disappointed in you."

Blue played. He addressed the team before the game, and his younger brother was in the locker room and on the sideline with the team, where Clark could keep an eye on him. The coaching staff reviewed an escape plan that had been prepared by police in case shots were fired at the game.

When the Wildcats took the field, they received a standing ovation.

"I will never forget walking out on that field," Clark says. "I was sobbing."

North Gaston won the game, 26-21. "A.J. was a rock that night," Clark says. "That wasn't a team of North Gaston. That was a team of A.J. Blue and his followers. When it was over, we got back to the locker room, and he lost it. I've never seen a young man weep like he wept that night."

Here is the crossroads. The game was over and now Blue actually had time to think about what had happened, about his brother who had been murdered. At the store, on the corner, in the neighborhood, he knew people who could avenge the crime.

But he didn't, because he believed there might be more to life than the code he'd been taught on Carpenter Avenue.

"Here's what people don't know about neighborhoods like mine," Blue says. "Guys wanted to do better. Guys didn't want me standing on the corner with them, or fighting, or making sales. They protected me like I was gold. They didn't want me to get in trouble."

Demarreo was killed in November. Three months later, A.J.'s son was born. He assumed he'd follow the normal path: drop out of school, find a way to provide for his baby. His mother quickly told him otherwise.

"You're staying in school," she told him. "You're going to play football, and you're going to graduate, and you're going to college."

And so he did. He was a highly sought-after recruit, a do-everything quarterback. When coaches called Blue, he'd take the phone out on the porch and put it on speakerphone. Dozens of college coaches have no idea that they weren't just talking to A.J. Blue. They were talking to the entire neighborhood.

"Guys were always standing around outside my house, so whenever I got a call from a college coach, I would go outside," he says. "Those guys had never experienced that, and I knew they were living life through me. Every time I talked to a coach, as soon as I hung up, they'd say, 'You have to commit!'"

That's how powerful the draw was to have a life outside of that corner of Gaston County. No matter the depth chart, no matter the location of the school, no matter the coaching philosophy – commit. Right now. Get out.

But it was Butch Davis who connected best with Blue and his family, and Blue pledged to be a Tar Heel. Coming to Chapel Hill required spending a year at Hargrave Military Academy, and multiple other schools told him he'd never make it. Come here, they told him, and you don't have to go to Hargrave. You can play right away, make the easy choice.

Blue wouldn't do it. He met lifelong friends at Hargrave, earned the academic credentials necessary to become a Tar Heel, and enrolled at Chapel Hill.

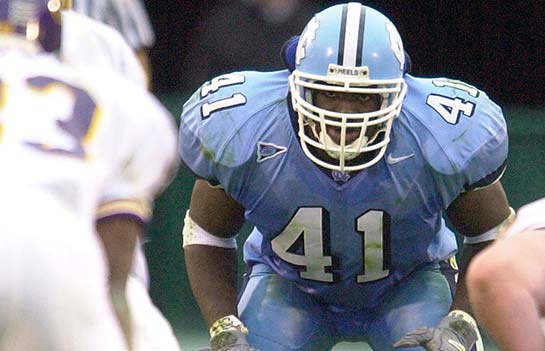

That's where his life changed. For the first time, he was exposed to teammates who came from a completely different background than him. "When I got to Carolina, my perspective wasn't big enough," he says. "My scholarship turned my life around. I started hanging out with guys who weren't from where I was from. I had to get out of that bubble. Some of the guys I hung out with would come out to Kenan at midnight and go through schemes and routes. I had never done that. Everything was new to me."

Blue played his final two seasons for Larry Fedora, and the two immediately bonded. The coach described Blue as "the best leader we have in our locker room" during Blue's senior season.

"A.J. was one of the most unique teammates I've ever had because of the level of respect he had from every single person in our locker room," says Matt Merletti, who was a Carolina teammate for three years. "He set the tone and culture for the team. Everyone tried to match his intensity in workouts and listened when he spoke because of the purpose he played and lived with."

Even as a college student, Blue was a doting father. His son, Amareon, lives in Gastonia. But he spent virtually every summer when Blue was a student living in Chapel Hill with his dad. There was no need for a babysitter; Amareon would attend summer school classes each day, and if he couldn't go with A.J., he'd go to class with Tre Boston, or Erik Highsmith, or one of dozens of other teammates. During the regular school year – and to this day – A.J. and Amareon talk every day on the phone. A.J.'s father has never been involved in his life, so he has a very simple parenting philosophy for Amareon: "I tell him I love him every single day," A.J. says.

This being the A.J. Blue story, of course, his Carolina football career wasn't without adversity. After switching from quarterback to running back as a freshman in 2009, he suffered a horrendous knee injury in his first game at the new position that forced him to miss the entire 2010 campaign.

He worked his way back and scored ten touchdowns as a junior while backing up Giovani Bernard. A back injury limited him during his senior season, sending him on an NFL free agent odyssey that included going to camp with the Washington Redskins, before an injury again intervened.

The football career, it appeared, was finished. Now what? Go back to Dallas and join the rest of the neighborhood in front of the store?

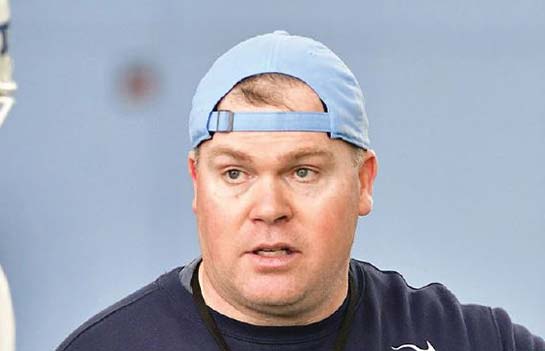

Blue wasn't willing to do that. He had a degree in communications from the University of North Carolina. He worked for a NASCAR crew before injuries again got in the way, then had a job at a glass factory. In the summer of 2015, he was on the way to a job interview at a uniform company. His cell phone battery had died, so he stopped at a Subway to grab a sandwich and plug in his phone. Almost as soon as the screen flickered to life, the phone rang. It was Fedora, offering him a job. He just finished his third season with the team, where you are most likely to see him bouncing around on the sideline during games.

"There is nothing I would rather be doing than being at Carolina with these guys, bringing crazy energy and creating some perspective for them," Blue says.

That perspective is a complex one. Blue knows his life changed when he left Dallas. But he also knows Dallas was home. He knows good people there who work hard to try and overcome their circumstances, but never received the opportunity he was given.

So many of his friends, who stood on that porch listening to the college coaches on the speakerphone, never made it out. He did. Why? He's not sure, but he knows he wants to take advantage of it. His life has changed. His son's life has changed. Somewhere in Gaston County, there's a kid who wants to be the next A.J. Blue instead of the next guy standing outside the store with a wad of bills. That's a powerful repudiation of the normal cycle.

Every day, Blue tries to remind a Tar Heel how lucky they are to be in this particular place.

"Nobody from my community or in my family ever went to college," Blue says. "I still can't believe that I got the opportunity to showcase my talent in front of thousands of people every Saturday. That's what I want to tell these guys. The whole opportunity we have here is so rare. Seize this moment and make the most of it. Being here, at North Carolina, is the opportunity of a lifetime."

More Stories

The impact of giving comes through in wonderful stories about Carolina student-athletes and coaches, as well as the donors who make their opportunities possible. Learn more about the life-changing impact you can have on a fellow Tar Heel through one of the features included here: