XS AND OS

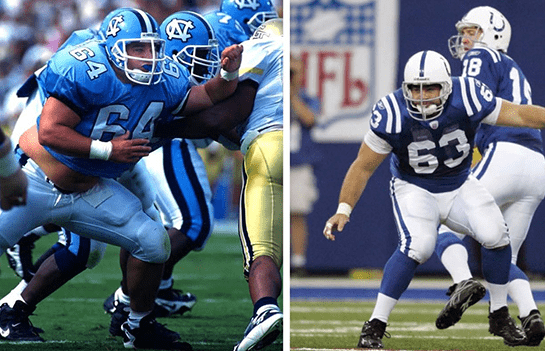

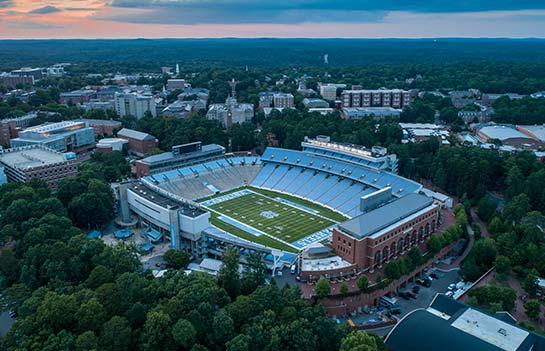

Mack Brown Designed His New Offense and Defense To Give the Tar Heels a Chance To Win Now

By: Lee Pace

You’ll hear the watchwords and catch phrases on the Tar Heels’ offense now along the lines of “chasing grass” and “playing instinctively” and “don’t blink.”

On defense they’ll talk of “destroying blocks” and “everyone’s a blitzer” and taking better angles and “killing the engine” with the perfect rugby tackle technique.

On both sides of the ball, coordinators Phil Longo and Jay Bateman speak of the appearance of complexity but the reality to their players of relative simplicity.

“We don’t want to handicap guys so they have to think so much they can’t be physical and aggressive and play downhill,” says Longo, the architect of the Tar Heels’ version of the Air Raid offense. “We as coaches don’t need to impress them with how much football we know. Give them what they need to know and let them go play.”

“To some offensive coordinators, it’s going to look like we have a hundred blitzes,” says Bateman, hired from Army to co-coordinate the defense along with Tommy Thigpen. “But we have six. But we’ll move guys around, use different fronts and different disguises. We’re going to create this belief that, ‘Gosh, there’s so much defense.’ But in the end, we’ll be simple and aggressive. We’ll solve our problems with aggression.”

The first year of Mack Brown’s return as the Tar Heels’ head coach will certainly be interesting from a schematic approach. The offense will stretch the field vertically but is committed to having the brawn and bulk to pound out three yards in the shadow of the goal line. The defense is officially listed as a “3-4” base, but Bateman shrugs that off as a simplistic effort to corn-hole a “type” and further notes that this same defense in his last stop at Army was hardly ever lining up with three down linemen.

“We’ve obviously struggled the last two years,” Brown says, referencing the Tar Heels’ five wins over the 2017-18 seasons under former head coach Larry Fedora. “So I had to figure out, ‘How can we catch up fast?’

“I think we have good answers with what Jay and Phil are doing. You look at what Army did the last few years, they had lesser players and stopped a lot of people. They took Oklahoma to overtime. And the Air Raid is what’s working now on offense. The best teams in the NFL are using elements of it. Phil is taking the best parts of the Air Raid’s ability to move the ball in the air and combining with the power running game. I like what we’re doing on both sides of the ball.”

Longo has put up prolific numbers running his version of the Air Raid, most recently at Sam Houston State in the Southland Conference and then Ole Miss in the SEC. At SHS from 2014-16, Longo’s offense shattered multiple school records, the 2016 team boasting the nation’s No. 1 total offense at nearly 550 yards a game. Ole Miss was a top-20 attack in both 2017-18, and the ’17 team was the nation’s fastest-scoring team with an average of 99 seconds per scoring drive.

Yet Longo prides himself on balance. His offense at Sam Houston State rushed for just over 3,800 yards in 2014 and ‘15. And you have to be good on the ground to put up the kind of red-zone numbers the ’17 Rebel offense did with a 95.3 percent conversion rate inside the 20 yard-line.

“There is a time and a place in the game where you have to be able to run the ball,” Longo says. “We’re always going to have that physical component in our offense. Always.”

“The term ‘Air Raid’ makes you think you throw it every time, and you don’t,” Brown adds. “It offers a good balance, and you can do either. A lot of it is taking what’s there.”

The offense is built around 28 basic plays with hundreds of variations with personnel groups, formations and motions. Longo likes the “don’t blink” mantra to emphasize to players that, no matter a good or bad result on a play, forget it, get the sign for the next snap and be ready to go in a hurry. In illustrating the core philosophy of the offense, he cites great athletes who never found their niche because they were handcuffed by structure and coaching overkill. He believes in framework and organization – but to a point far less than most coaches.

“It’s essential they play instinctively, and the less a player is thinking on the field, the faster he’s going to be and the better he’s going to be,” Longo says. “The guys who have that pure athletic talent, go let them display it. Never restrict them and handcuff them mentally. I hate to see a kid confined by as many rules and checks and things to think about as you find so many places.

“If a player is playing instinctively, he owns that play. If he only has 28 of them, he should be playing instinctively and doing it without thinking or slowing down.”

One system might specify a proper post-route as a receiver running downfield x-number of yards, then angling toward the “post” or other landmark. Carolina’s system has that receiver running downfield and then adjusting midstream, depending on the reaction of the defensive back.

“It takes a lot of discipline to give someone freedom,” Longo says. “To tell them run 10 yards down the field and make a left-hand turn and run a post, and draw it up and insist that’s how they run the route, that does not take as much discipline as when you tell a receiver you’re going to push vertically and when there’s space, stick your foot in the ground and go find the grass. You’re giving them an opportunity to get open.”

Longo stresses that the Tar Heel Air Raid can vary from year to year, depending on the strengths and weaknesses of that particular roster. Carolina has a quality running back corps this fall led by senior Antonio Williams, junior Michael Carter and sophomore Javonte Williams, so expect to see them showcased come Aug. 31 and into September.

“There’s a misunderstanding about the Air Raid,” says running backs coach Robert Gillespie. “It’s all about numbers. You have to make a defense defend an entire field. The safeties aren’t as worried about runfits. They have to do a great job defending the entire field with RPOs, and that opens up a lot of running lanes. You take an extra defender out of the box, and the running back is running to space. A lot of the runs we had in spring ball were big gains.”

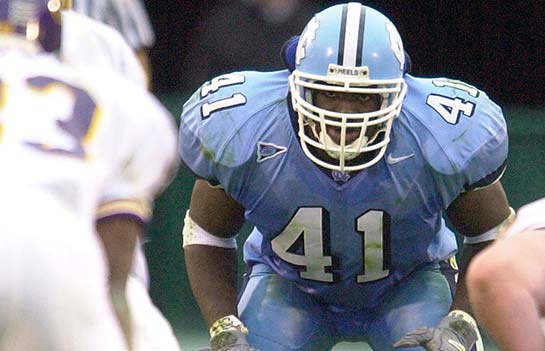

Whatever success the defense enjoys in coming years will be built just as Brown’s juggernaut defenses were when he was at Carolina the first time in the 1990s – with recruiting stud athletes, particularly along the defensive front. But in the meantime, Bateman believes there are some “great equalizers” that can help Carolina play better defense and improve upon its 448 yards a game allowed in 2018. One is an emphasis on block-destruction and tackling method; another is a schematic mindset that he likens to playing like “rebel warriors.”

After his first year at Army in 2014 when the Black Knights were No. 90 nationally in total defense, Bateman drew on ideas he’d seen from Alabama’s and Ohio State’s practices and instituted a regimen of five minutes of carefully choreographed, intense and fast-paced drills on shucking blocks and taking ball-carriers to the ground.

He themed the regimen “The Difference” and slotted it at the beginning of practice every day – while the players were still fresh and to set a mindset for the day.

“I got to thinking about it and said, ‘You know what, if we tackle really well and we get off blocks really well, the rest of it doesn’t matter,’” he says. “You’ve got to whip blocks and got to tackle really well. I feel like you get what you emphasize. This would be what would make us different from every other defense in the country. We’re going to be the best tacklers and be the hardest to block.”

Over the next four seasons, Army would be among the nation’s leaders defensively and rank No. 4 in total defense in 2016 and No. 8 in 2018, both years allowing under 300 yards a game.

“If you watch our film at Army, you’ll see kids who are really hard to block, and are really good tacklers,” Bateman says. “When I got here and I watched the film, the thing I knew I could improve was our angles to the football, our tackling and our block destruction. I want us to be known as a violent tackling team. When it flips, you can tell because you suck the air out of the running game.”

A second watershed decision further built the Black Knights’ defensive tradition – that of overhauling the team’s tackling technique. Army’s defense had 14 games total missed by various players because of concussions in 2014. Bateman watched Seattle Seahawks games and read about Coach Pete Carroll’s tackling philosophy. The Seahawks were using what they called the “Hawk” technique of attacking the runner’s thighs with the defender’s nearest shoulder, wrapping his legs with both arms and driving or rolling the runner to the ground. The technique is more popularly known as the “rugby” tackle because it’s the method preferred by rugby players, who never wear helmets and need to keep their heads out of harm’s way.

Bateman and his staff learned the rugby tackle and taught it to their players going into the 2015 season.

“The next year, we had one player miss a game with a head injury,” Bateman says. “That’s huge. There were always some things about tackling as it had been taught forever that didn’t make sense to me. I’m supposed to run inside-out on the ball and then get my head across. That’s physically impossible. That always caused me conflict. The game of football was so under attack, as a coach if you don’t do something different, you’re sticking your head in the sand. The last couple of years at Army, one or two kids missed one game for concussions and we’re playing at a higher level and playing against better opponents. You say, ‘Gosh, this has got to be a piece of it.’”

It’s only after emphasizing the importance of warding off blocks and taking runners to the ground with precision that Bateman even broaches the subject of scheme, and even then he says that identifying the Tar Heels’ base as a “3-4” is almost superfluous.

“Scheme is a really over-rated thing,” he says. “If our scheme is not multiple enough to put our best 11 on the field, then I should be fired. People say, ‘Are you 3-4?’ I say, ‘Yeah, sure, we’re 3-4, but we line up in everything.’ It just depends on what’s our best call and who are we playing? Last year, we were in two-down more than anything.”

What Bateman will say, though, is that the Tar Heels will not play defense in a “Tampa 2” mode of having two deep safeties, playing lots of zone, trying to generate heat with four down linemen and keeping everything underneath.

“If you’re just dropping in what I call ‘vision coverage’ where I’m seeing the ball and I’m breaking, you used to be able do that and be pretty good,” he says. “The Tampa Bay Buccaneers won a Super Bowl doing that. Today, though, the ball comes out so fast and quarterbacks are so accurate and receivers are so good in space.

“Our defense will be like rebel warriors, we kind of come from everywhere and we try to bait you into things, cause confusion, cause havoc, infiltrate from within. You try to create negative plays, you try to create incompletions, you try to create sacks. If you do that, you’re in pretty good shape.”

And the first rule: Everyone is a blitzer.

“I love it,” says Trey Morrison, a nickel back. “We can come from anywhere on the field. I’ve lined up everywhere this spring.”

“I love being with coordinators who think ‘attack,’” adds cornerbacks coach Dré Bly. “That’s what Jay did at Army and that’s what made him successful. We have a variety of looks and bring guys from all over the field. Our guys are embracing the moment and excited about this new opportunity.”

The combination of spring practice and August scrimmages as these two systems collide against one another is sure to create some angst in Mack Brown’s core.

Celebrating a big play on one side of the ball might be whistling past the graveyard on the other. In due time we’ll see these playbooks and philosophies evolve against big boy football teams.

More Stories

The impact of giving comes through in wonderful stories about Carolina student-athletes and coaches, as well as the donors who make their opportunities possible. Learn more about the life-changing impact you can have on a fellow Tar Heel through one of the features included here: