Extra Points: The Monk Legacy

By: Lee Place

Tommy Thigpen was a graduate assistant at Carolina in 1998-99 after his playing career for the Tar Heels and in the NFL and remembers one linebacker in particular from that era. Quincy Monk at the time was just getting his bearings after being red-shirted in 1997 and starting to play on special teams in 1998.

"He was super mature and confident," Thigpen remembers. "He had a great demeanor about himself. Physically, he looked like Ray Jacobs. He had zero body fat, was fast and really smart."

More than two decades later, Thigpen is coaching the Tar Heel linebackers on Mack Brown's staff and everyday walks into a meeting room on the second floor of the Kenan Football Center that is dedicated to Monk's memory.

After a three-year career in the NFL and a return to the Triangle area to begin a business career and to raise a family, Monk died in November 2015 of adenocarcinoma, an aggressive form of cancer. The Quincy Monk Inside Linebacker Room was dedicated in March through gifts made by the people Monk impacted the most – his teammates. Those teammates and his coaches saw firsthand the quality football player that Quincy Monk was, and more importantly, the genuine person he was.

"Seeing what his teammates have done to honor him with this legacy tribute is really special," says Brian Chacos, a former teammate of Monk's and currently a major gift director with The Rams Club. "I love seeing our former student-athletes giving back to Carolina, and in this case, honoring an incredible man like Quincy."

Today Thigpen harkens to his memory of Monk and encourages the linebackers in his charge to play football and conduct their lives at the high standards set by Monk, who ended his Tar Heel career by starting at linebacker on the 2001 team that whipped Florida State at home and thumped Auburn in the Peach Bowl.

"Leave a legacy," is Thigpen's message. "Make sure generations of players and family know your name. When you bring your family here, it will be the place you're most proud of."

Monk was a native of Jacksonville, N.C., and excelled in athletics during every sports season at White Oak High. He was a quarterback in football, a center in basketball, and threw the shot put. He was team MVP in football and basketball and all-conference and all-area in both sports his junior and senior years.

Danny Davis played both sports as well for Manteo High just up the coast and got a sneak peek at his future Carolina football teammate during a summer basketball camp in 1996.

"Quincy was a beast," says Davis, a member with Monk of the 1997 Carolina recruiting class. "The crazy thing is, he may had been better at basketball than football. He was unstoppable."

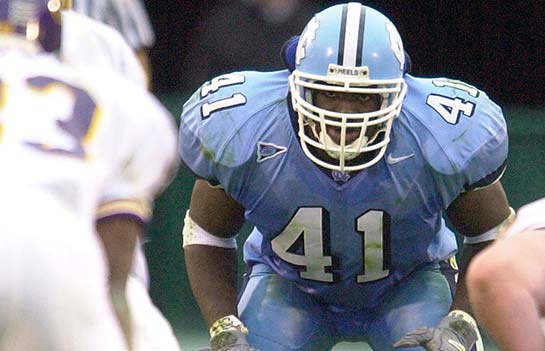

That class also included Kory Bailey, Errol Hood, Billy-Dee Greenwood, Merceda Perry and Joey Evans, among others. They quickly learned upon arrival in Chapel Hill that summer that there was something different about Monk, who stood 6-foot-3 and would develop from 205 pounds as a freshman to 240 as a senior.

"Off the field he was a big, friendly teddy bear," Davis says. "People would probably think of him as a scary guy if you walked past him on the street, but as soon as you had a few conversations with him, you realized how special he was.

"After freshmen two-a-days is when I realized he was the nicest giant ever. He always picked up others when down. He never had a bad thing to say. He came to work every day and was 'all in' at all times."

Bailey, a receiver from Durham, was amazed to learn that big, athletic linebacker had starred on offense in high school.

"I can't imagine trying to tackle him," Bailey says. "You were immediately drawn to him. He's got that big, bright smile, and when he laughed, he laughed with his entire body. He was just a real pleasure of a guy to be around. People gravitated toward him. He was just magnetic that way."

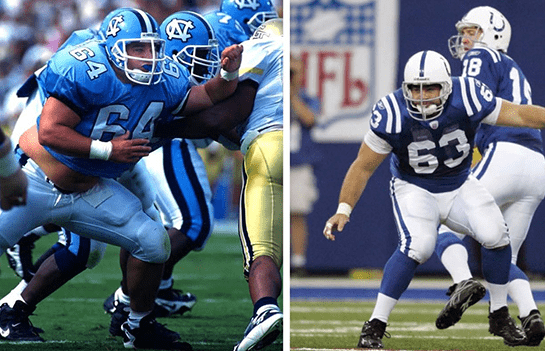

Monk started the final nine games of his junior season in 2000 season and made 15 tackles at Florida State. That was Carl Torbush's last year as the Tar Heels' head coach, and he was replaced by John Bunting. As a senior in 2001, Monk thrived as the starting middle linebacker and made 125 tackles. He was the leader of a defense that nabbed five turnovers and held Florida State to one touchdown in a 41-7 rout in the fourth game of the season. That followed opening losses to Oklahoma, Maryland and Texas and catapulted the Tar Heels to a five-game win streak. That season also marked the emergence of a walk-on linebacker, David Thornton, who earned a scholarship and went on to a long career in the NFL.

"Quincy led the team in enthusiasm, in doing what's right, he was a model for other players," Bunting remembers. "He was always motivated, always trying to get better. He had quite a bit of talent. Quincy ran the defense and he nursed David Thornton along and was a mentor to David.

"After the loss at Texas in the third game, I blistered that defense pretty good. We were 0-3 and our next game against SMU was postponed after 9/11. So, we had Florida State coming to Chapel Hill. I grabbed Quincy and David. I said, 'You guys have gotta do something.' We had a great week of practice and a very simple game plan. The way the defense played in that game was just incredible, and Quincy was all over the field."

Monk was drafted in the seventh round of the 2002 NFL draft and played two years with the New York Giants and one with the Houston Texans. A decade later, he was married to Lisa and the father to daughter Naomi and son Aiden, and was working in Raleigh for the Select Group, a technical services firm. He suffered a stroke in June 2015, and doctors discovered he had cancer.

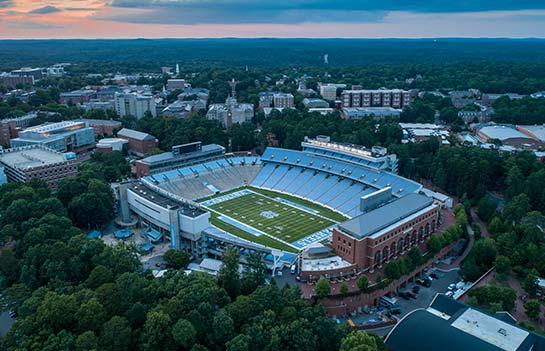

Monk was in and out of hospitals all summer and early fall and appeared to be making steady progress for a recovery when he was invited to be a "Kenan Legend" at the Wake Forest game in mid-October. The afternoon before, he addressed the Tar Heel squad during its walk-through in the stadium.

Monk told the players of a new perspective that comes from facing mortality, that he never gave up on the field in Kenan Stadium and wasn't going to now. He told them of his senior season in 2001, when the Tar Heels won five in a row but then got sloppy and big-headed and lost two straight.

"Don't take your foot off the gas pedal," he told the Tar Heels, who at that point were halfway through an eleven-game win streak that culminated in winning the ACC Coastal Division title.

The next night in a suite in the Blue Zone with former teammates, Monk talked of the "brotherhood" of Tar Heel football and that his life always circled back to Kenan Stadium and his fellow lettermen. Sadly, he lost his battle five weeks later.

"Quincy truly embodied 'the Carolina way' and everything the Carolina football family stands for," Bailey says. "He was the most upstanding guy you can imagine. He played the game the right way, he worked out the right way, he studied the right way. He was the anchor of our class."

His teammates marveled at the attitude he portrayed even during his final days.

"I visited the hospital and he still had a smile on his face," Greenwood says. "He still had a lot of strength and perseverance. It was great for me to have the opportunity to see him before he passed and be reminded of what a great teammate and great friend he was."

More Stories

The impact of giving comes through in wonderful stories about Carolina student-athletes and coaches, as well as the donors who make their opportunities possible. Learn more about the life-changing impact you can have on a fellow Tar Heel through one of the features included here: